For several decades, forest landscape restoration (FLR) has been used as an integrated approach to improve the resilience of landscapes and the livelihoods they support. In our resource-constrained world, under the threat of climate change, restoring degraded ecosystems is key to safeguarding natural capital and ensuring food and nutrition security.

Some progress has been made towards achieving global hunger targets, as the number of undernourished people has fallen to under 800 million from between the time of the World Food Summit in 1996 through the era of the Millennium Development Goals to 2015. However, as we transition to the new Sustainable Development Agenda (2015-2030) the fight against eradicating hunger continues as about 795 million people globally still remain undernourished, 780 million of whom live in developing countries (FAO, IFAD, WFP, 2015). Poverty is a key indicator of hunger. But poverty is the result of unresolved global challenges - whether conflict, sluggish economic development, climate change, rising food prices, overharvested ecosystems or weather-induced disasters - that underlie economic growth and development and must be addressed to foster global sustainability and ensure food security. Alongside these challenges, the current world population is projected to increase from 7.2 billion to 9.6 billion by 2050 (UN DESA, Population Division, 2015) placing continuing pressure on already depleting natural resources. The majority of the world's poor live in rural areas in low-income countries where agriculture remains the main source of income and employment for about 2.5 billion people (IFPRI, 2015). Future agricultural production will have to rise to meet this growing demand for food.

It is well known that climate change threatens global food systems, with plenty of evidence worldwide indicating an increase in droughts and a decrease in crop yields. According to current projections, if the world becomes warmer than the current trend by 2050, the decline in crop yields will be further exacerbated. Without the capacity for mitigating climate change, it will become even more difficult to expand and intensify food production due to water scarcity and land degradation.

There are more than 2 billion hectares of deforested and degraded land globally (GPFLR, 2013) directly affecting 1.5 billion people (UNCCD, 2014). Global deforestation accounts for about 20 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Currently, about 25% of total global emissions arise from the land use sector and about 40% of the world's agricultural land is already degraded. Land degradation affects the functionality and productivity of food systems, on which we depend for livelihoods.Population pressure and the expansion and intensification of agricultural practices, along with the impacts of climate change, pose a range of threats to the security of food, energy, water and resources. Meeting the global demand for food, either through agriculture expansion or agricultural intensification without taking environmental risks is very challenging. Massive loss of forests and land degradation are evident across the world. Reducing the current trend in deforestation and land degradation will require economic incentives, and change in practices and policies that induce preservation and conservation and encourage restoration of forest and forest landscapes.

FLR is a coherent approach that has the potential to mitigate the underlying conditions of erosion, soil degradation and nutrient depletion, and enhance the opportunity for obtaining greater output from degraded land. It is a long-term process of regaining ecological functionality and enhancing human well-being across deforested or degraded forest landscapes. It focuses on restoring forest functionality: that is, the goods, services and ecological processes that forests can provide at the broader landscape level, as opposed to solely promoting increased tree cover at a particular location (Maginnis & Jackson, 2002). It is not just about planting trees - it involves tailoring the solution to the context in order to bring back or improve the productivity of landscapes that are deforested or degraded so they can sustainably meet the needs of people.

There is increasing evidence that FLR interventions deliver multiple benefits to the environment and society. The framework offers a wide range of restoration options based on the characteristics of each agro-ecological zone. For example:

If the land, due to deforestation or degradation, requires increasing forest cover, then a suitable intervention could be to plant forests and woodlots, or undertake silviculture or natural regeneration to increase the number of trees in an area. This is highly important for approximately 1.6 billion forest-dependent people worldwide who in some way depend on high-economic value tree species for income generation, fuelwood, timber, medicines and fruit; for high nutrition intake as well as enhancing habitat.

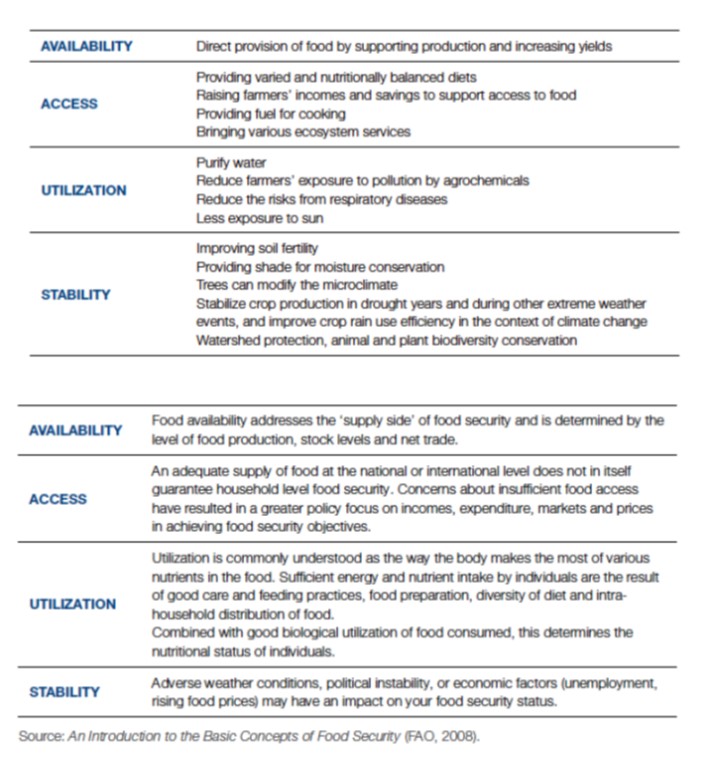

For degraded agricultural land, improved fallow or agroforestry practices are suitable for bringing back the biological productivity of the land by increasing soil fertility, enhancing water retention and improving crop productivity. This can directly benefit more than 1 billion people who practice such farming systems. Because FLR involves entire landscapes in all jurisdictions, it also offers watershed protection and enhancement of mangroves along coastal areas. Mangrove restoration not only tends to safeguard the coastal areas against weather-induced catastrophic events but enhancing food security through forest landscape restoration: Lessons from Burkina Faso, Brazil, Guatemala, Viet Nam, Ghana, Ethiopia and Philippines also improves the livelihoods of coastal communities. At a watershed level, FLR enhances groundwater levels while protecting downstream communities and hydraulic infrastructure. In addition to these social and ecological benefits, FLR's long-term benefit to the environment is its potential for carbon sequestration.

The Global Partnership for Forest Landscape Restoration estimated that more than 2 billion hectares of degraded land is available for restoration globally - an area larger than South America! Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR) is the process of regaining ecological functionality and enhancing human well-being across deforested or degraded forest landscapes. The Restoration Opportunities Assessment Methodology (ROAM), developed by IUCN and the World Resources Institute (WRI), is the primary framework for building a forest landscape restoration programme from the ground-up. This in-depth step-wise methodology has proven effective in assessing and laying the groundwork for FLR interventions with practical steps for diverse stakeholders to restore landscapes at any scale.

ROAM is a flexible and cost-effective analytic process for identifying restoration opportunities at national or sub-national levels, as well as describing how those opportunities relate to food, water and energy security. The application of ROAM generates good context-specific knowledge relevant to understanding and addressing forest and land-use planning and management. The assessment also provides a participatory framework that can be used to set common restoration goals that address immediate priorities, such as livelihoods.

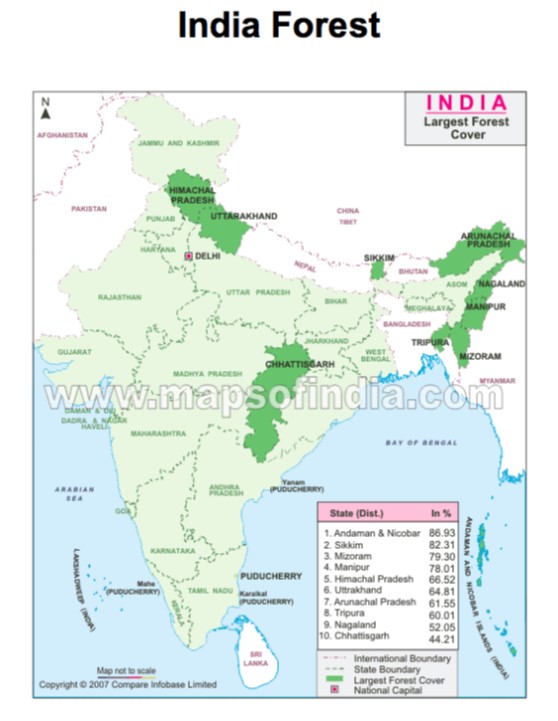

In India, IUCN is conducting a sub-national ROAM assessment in the State of Uttarakhand. The state was selected because it has immense potential for successful land-use and land management driven mitigation and adaptation programmes.

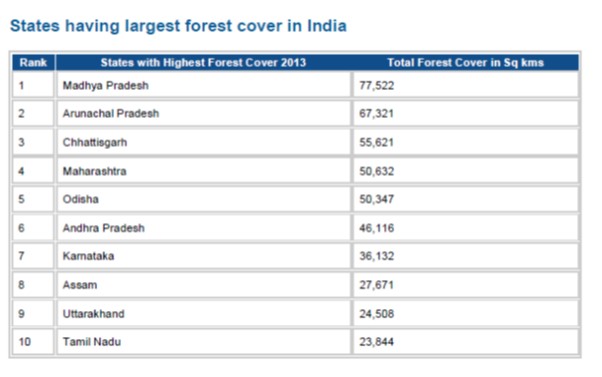

In tropical areas, forests are increasingly subjected to deforestation and degradation with adverse socio-economic and environmental impacts. Widespread forest degradation in developing countries remains poorly understood and quantified. Degraded forest constitutes a considerable portion of forestlands here. In India, degraded forests constitute 41% of the total forest cover.

In India, realizing the need for conservation and regeneration, several programmes have been implemented at the government and non-government levels. Following the enactment of the Forest Conservation Act in 1980, diversion of forestland declined drastically to around 15 500 ha per annum from 150 000 ha per annum prior to 1980. Total area under forest has nearly stabilized at around 64 million ha. Thus restoration of degraded lands assumes priority in planning and implementation. The key issues to be addressed are change in forest composition because of selective overexploitation, loss of natural regeneration, low growing stock, productivity and also because of the current initiatives at the government and non-government levels dealing with deforestation and forest degradation.Sangini Foundation with its partner ecosystem (MoEF, State Forest Departments, G.B. Pant National Institute of Himalayan Environment and Sustainable Development , TERI, Forest Research Institute etc) will use the ROAM framework to identify states like Uttarakhand and Karnataka (Western Ghats) to undertake community led, women-oriented FLR activities focusing on species like Bamboo, Jatropha etc.

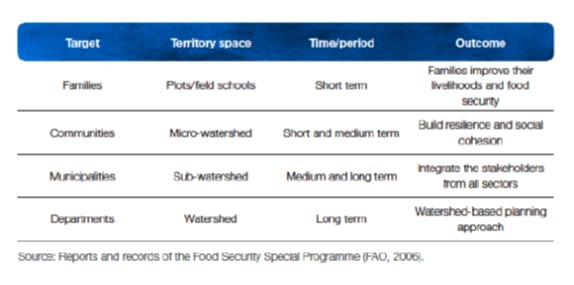

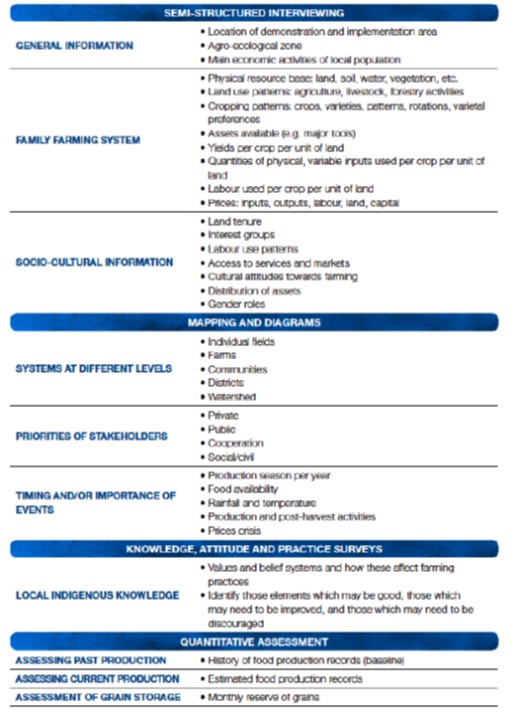

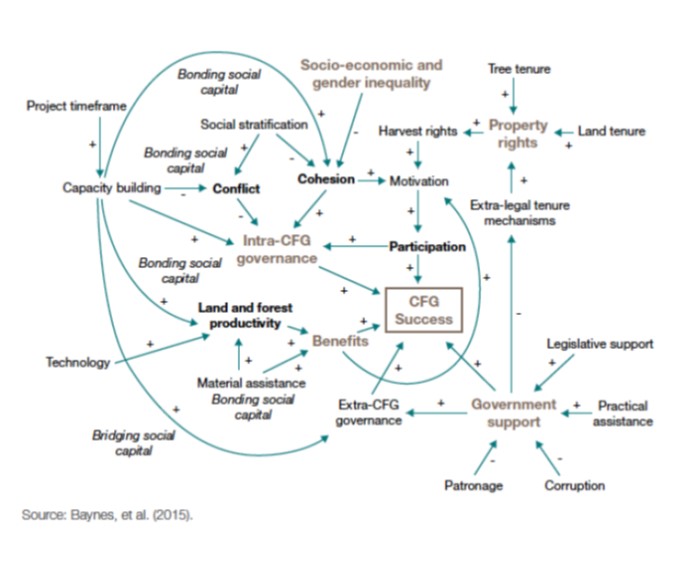

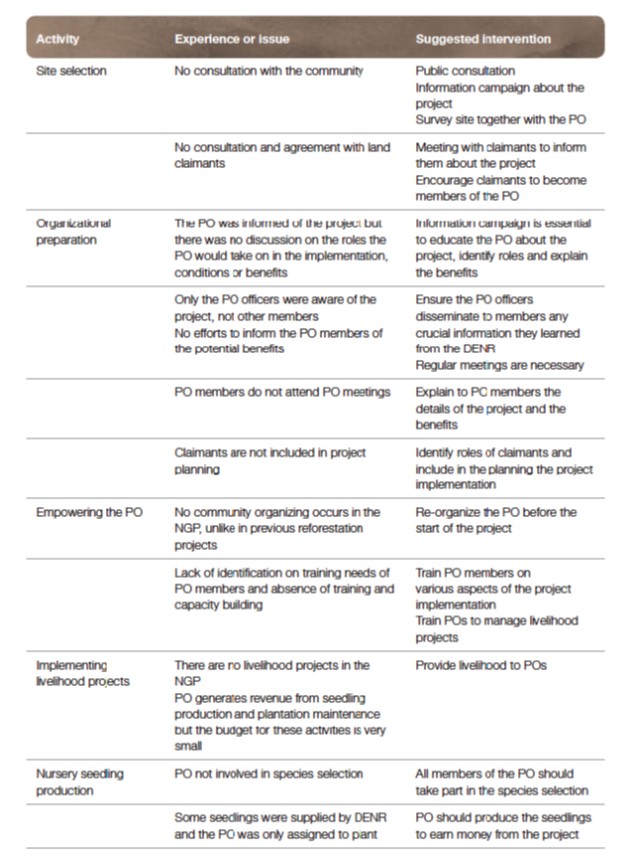

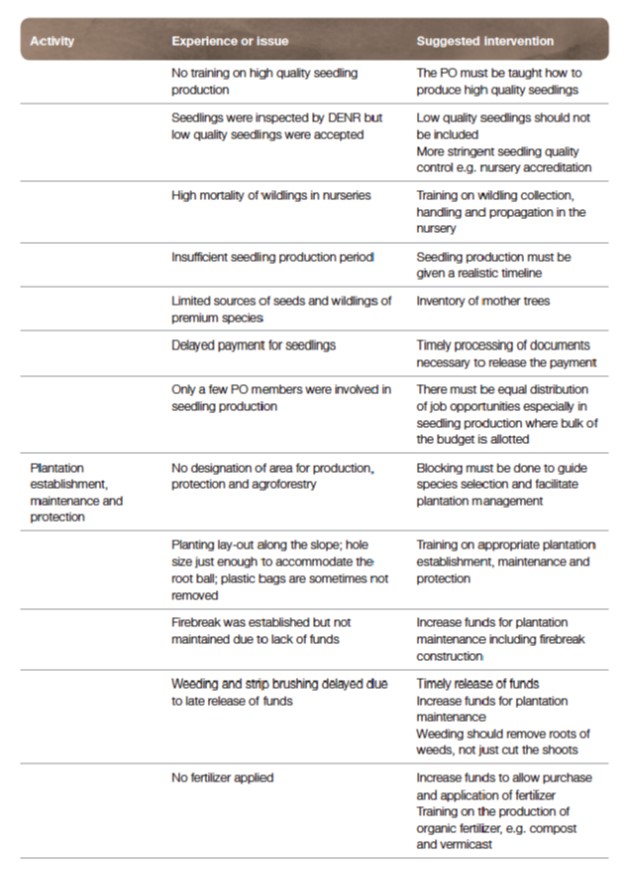

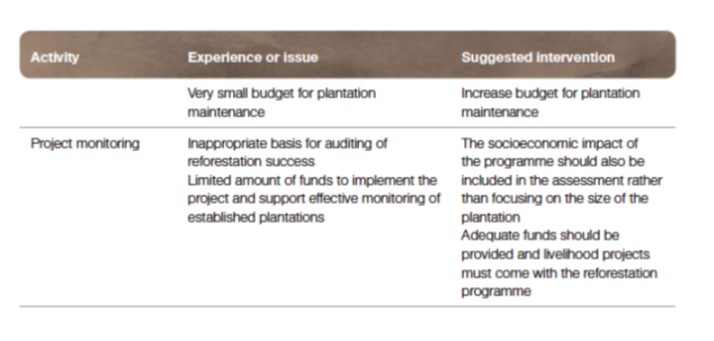

Our scientific approach to FLR implementation is captured in the following tables :